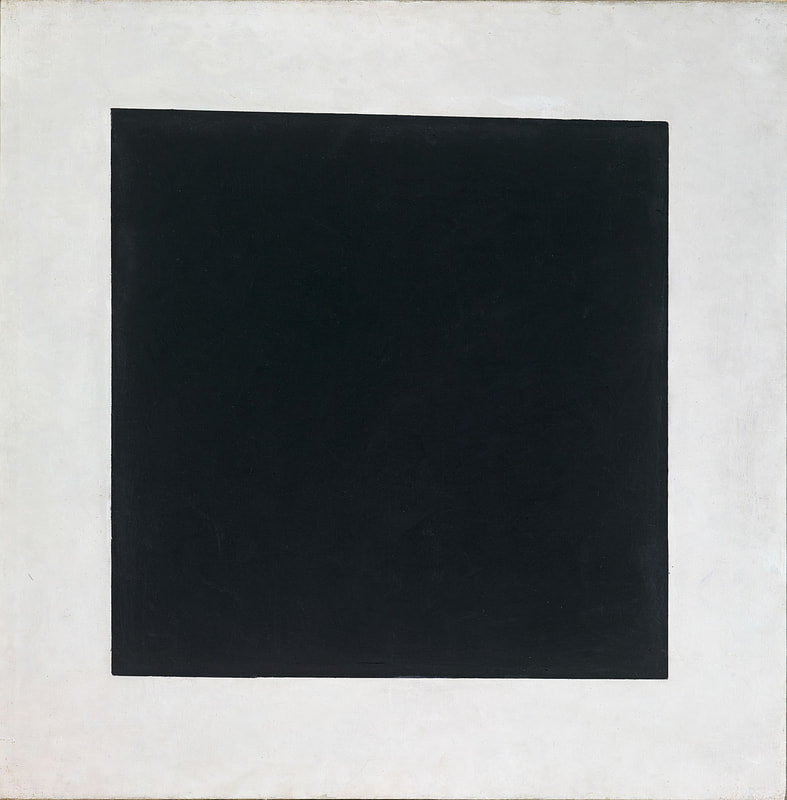

Site For A Life Still: Andrew Dadson at the Contemporary Art Gallery, by Holly Marie Armishaw17/11/2017 On a typical dark, rainy Vancouver Sunday afternoon in 2011 I had the pleasure of my first genuine encounter with the work of Andrew Dadson. As I gathered with other members of the Contemporary Art Society of Vancouver for a studio visit in Dadson’s garage, which doubled as his studio at the time, I listened carefully as he shared the process and meaning behind his art practice. As he spoke of the representation of the void in his work, I experienced that moment of exhilaration when I am able to make an intellectual connection with someone else’s work. My mind immediately conjured images from Stephen Hawking’s writings on dark matter and wormholes. I have been quietly following Dadson’s work ever since that day as it has made its way to various international exhibitions and art fairs. Six years later, upon viewing his solo exhibition, I am as impressed with Dadson’s practice today as I was in 2011. As you enter the Contemporary Art Gallery during Andrew Dadson’s solo show “Site For Still Life”, curated by Director Nigel Prince, the first thing that you’ll notice is the soft, violet aura which emanates from the B.C. Binning wing. One is drawn like a moth to a flame towards a series of eight potted houseplants, dispersed atop a low platform at the far end of the gallery. Though varying in type and size, each plant and its pot are painted uniformly in white, biodegradable paint. The plants are properly potted in moist, fertilized soil and are illuminated by LED grow lights placed at either side of the platform. This is a living sculpture – a growing trend among 20th century contemporary art, which uses plants and animals as its unwitting subjects. As these plants grow, their artificial shells crack from the internal pressure leaving parts of the leaves exposed and paint debris scattered below. “Houseplants” (2017) is an extension of Dadson’s practice, which traverses the delineation between painting and sculpture. Dadson is perhaps best known for his thick, sculptural paintings created by an additive process of multiple layers of various colours of paint. A process-based artist, his technique is revealed in the application and careful placement of the paint itself. After the paint is applied most of it is then scraped away from the surface of the canvas and onto the edges, thus extending the painting beyond the canvas itself, creating a thick, multi-colored crust. Once the layering is complete, in an act of negation, Dadson applies the thick painting into a second raw canvas before removing the original one. What was once the bottom layer of the painting then becomes the top. An indentation is left where the thick primary canvas once was, creating a concave low-relief sculpture. The result is one of his signature “Restretch” paintings. The final, top layer of paint showing is always either white or black, bringing the viewer back into the void of abstraction recalling Malevich’s seminal work “The Black Square” (1915). The four small “Restretch” paintings in “Site For A Still Life” were created using Dadson’s signature process, except that he replaced multi-colored paint layers with raw materials such as locally sourced mulch, gravel and soil in an homage to Arte Povera. Dadson’s use of paint and soils can easily be related to his landscape interventions, such as “Black Painted Lawn” (2006) and “Black Hill” (2014), in which he spray painted sections of outdoor private and public property with non-toxic acrylic paint, then photo-documented the work for posterity. The visual essence of these installations parallels his monochromatic works on canvas. While this act of obliteration of still recalls Malevich’s “Black Square”, Dadson almost intuitively realizes in his work that the void, or nothingness, can only be defined in comparison to something, hence leaving the rough edges to define or frame the negative. In the Alvin Balkind wing at the CAG, Dadson has darkened the gallery and painted the walls black. In the centre, two projectors face opposite walls running the same reel of film. While one projects a sunrise the other, a sunset; at times it is difficult to tell which is which. Both time-lapsed films contain a partly cloudy sky, and a large glowing orb, all rendered in monochromatic tinted orange. “Sunrise/Sunset” (2015/17) is a simple, but powerful metaphor for the cyclical opposing forces of nature and the temporality of existence. Returning to the B.C. Binning wing, two large monochromatic paintings suddenly come into focus. “Silver Mass” (2017) and “Double Half (2017) seem almost representational, as far as abstract paintings go. On the thick silver coated mass of paint a circular form appears in diminished view above a partial view of a much larger, assumingly closer, circular form. One can easily imagine that this is a view of one planet or moon, as seen from another. This premise is reinforced by marks that could easily be seen as moon craters. “Double Half”, whose final layer is rendered in white, seems again to represent celestial bodies, this time as seen from outer space. In a subtractive method, Dadson has gouged away small areas of the top paint layer to reveal a deep blue beneath, suggesting far away galaxies and stars. The end result is as if the artist has rendered a view from space, in a reversal of dark and light. Noting how the artist focused this exhibit on atmosphere, (sun) light, earth (soil) and plants, all basic elements of survival – a clearer and profounder sense of Dadson’s work is revealed. Upon carefully viewing each work in the exhibit, the “Houseplants” installation takes on new meaning. The scene of quiet, motionless life forms bathed in an otherworldly light have a sublime effect. My thoughts return to Stephen Hawking and his proclamation in the spring of 2017 that humans must look to inhabit other planets within the next 100 years in order to survive before life on earth as we know it is decimated. Dadson seems more optimistic in his outlook for the humankind future than Malevich did. Where it is possible to sustain plant life, there is hope. Until that time, earth is still a site for life.

- Holly Marie Armishaw (October 2017)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Holly Marie Armishaw

Based in Vancouver, Canada, Holly Marie Armishaw is a contemporary artist, art writer, francophile, and world traveler. Through rigorous exploration of inspiration from international sources of art and culture, she infuses her insights with a critical eye as she discusses global trends. Both her art and writing are informed by attending a continuous array of art exhibitions, lectures, fairs and biennales, both at home and abroad. Articles

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed