|

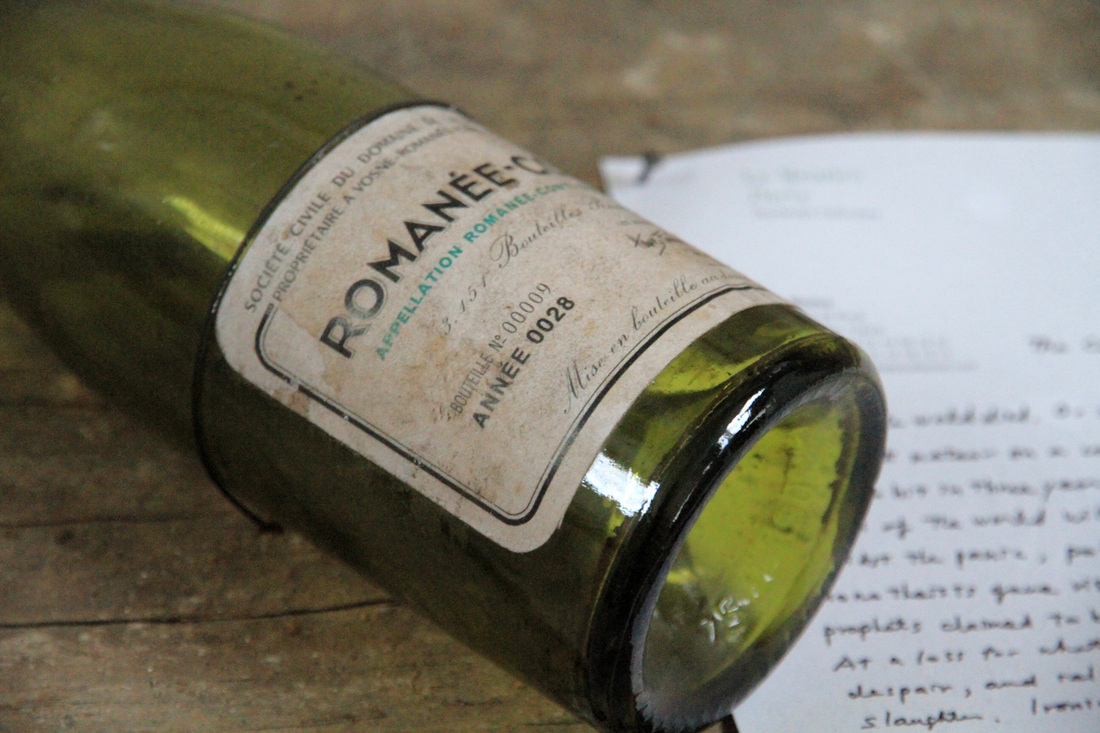

Hiroshi Sugimoto is one of the world’s most renowned photographic artists. He is masterful both in the technical precision of his works and in concept. He is best known for his long-duration exposures, such as those that are created in grandiose theater settings, opening his shutter for the entire duration of a film, which results in a beautifully detailed setting with a pure ray of light emitting from the screen. Using a similar technique, he has also created a series of seascapes; the duration of the exposure cancels out any and all details of the waves, photographically annihilating any potential life form from the image. The result is a minimalist composition with a clean horizon line, separating ocean from sky. It is with one of these seascapes that our journey into Sugimoto’s solo exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo begins. Upon entering the subterranean space of Paris’ iconic contemporary art institution, it is immediately evident that this is not a typical photography exhibit. In fact, photographs play a minimal role in this wholly immersive environment. We find ourselves taking on the role of archeologists in the post-apocalyptic realm that Hiroshi Sugimoto has created. The exhibition area is lit only by the natural light emitting from the skylights. On evenings when the gallery is open late, visitors are given flashlights with which to explore the exhibit, further engaging their senses and imagination in this mysterious realm, as it would be if one were to find themselves suddenly with no electricity available. I hesitate to use the word “exhibit” for this immersive environment as it is so far from the traditional formal use of the word when used in reference to art. However, many of its elements include artifacts from Sugimoto’s personal collection, indeed placed “on exhibit” for us to find in the wake of the apocalypse. Sugimoto invites us to imagine ourselves in this situation and has left clues for us to discover to piece together the story of “what happened”. Survival aids can be found around the space, including a bottle of preserved air. Amidst the ruins we find hand-written letters left behind from various individuals who relayed their final thoughts on the day that the world ended. At the end of the world as we know it, chaos reigns supreme. The natural world clearly has us at its mercy. For a moment, Sugimoto returns to his role as photographer, with his “Lightening Field” photographs, exposed through electromagnetic waves one of them is aptly placed behind a figure of the God of Thunder, further alluding to the idea that the human race has been metaphorically and perhaps literally ‘struck down’. Throughout the exhibition environment, many explanations can be found for the state in which we find ourselves: a meteor which has crashed through the skylight and continued it’s course blasting a hole in the gallery floor to reveal a hidden cavern; empty beehives; relics of war and most disturbingly, a "Japanese Hunting License" proclaiming open-season on the Japanese people. Where did we go wrong? Fossils of giant insects raise the question if they will once again rule the world when we are gone. Most riveting though are the evidences of how the last survivors tried to cope. Tiny vials containing supposed human DNA are hidden throughout the space, in hopes that the human race can be re-activated again in the future by any survivors. The impacts at the end are substantial, sex plays a key role in our survival; hermaphrodite bodies can be found strapped down, with gas masks or other respiratory aids. Others have accepted their tragic fates and have done the only thing they can think do – spend their last evening on earth drinking with friends. In case we don’t get the reference, Sugimoto has provided a panorama of images depicting “The Last Supper” - their photographic emulsions damaged by contact with liquid. A long table can be found strewn with empty bottles. At closer scrutiny we come across an important clue, a vintage date on a bottle of wine marked year “0028”. In a post-apocalyptic world all currency systems are affected and the art world is no exception. Art no longer holds the values we have ascribed to it. What was once considered a priceless pop art object now holds more value as a last meal. As we near the end of the exhibition we are left feeling lost, confused, alone and solemn. We have been hit hard in the gut through the confrontation of our own demise as we think about returning to the surface and emerging out into the city again to face the daily media blasts of the most recent and recurrent threats to global security. Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in Tokyo, Japan in 1948. This fact becomes relevant when we consider that he was born just 3 years after the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Growing up in a post-nuclear society would certainly give one cause to consider the looming threat of human extinction. As we near the end of the exhibition we approach one last object, placed on a plinth in the centre of the final stretch. The position in which it has been displayed indicates that this is a very important element. It is a small sculpture of stacked crystal prisms. As the clouds are clearing overhead and the sun begins to emerge through the skylights, a beam of light hits the prism releasing a small rainbow of colour, a symbol of hope. (Not only is light necessary for sustaining life, but is it also an essential element in the photographic process.) As we view the mid-sphere the centre splits into two visual fields, separated by a clear horizon line; no details, just earth and sky. All details have been obliterated, as they might be in the event of a nuclear disaster, just as they were in the first piece in the exhibit. In this we find a new beginning. As we follow the final corridor of the space, we find ourselves back at the beginning of the exhibit, where we first saw Sugimoto’s “Seascape” and the journey begins again. Although this exhibition was something of a surprise, Hiroshi Sugimoto has kept true to his most definitive themes: an encapsulation of time and the cyclical nature of death and re-birth. This impressive exhibition comes full circle, though an experience that has the familiarity of a great film or film. We leave our journey in awe of its profundity. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s exhibit “Aujourd’hui, le monde est mort [Lost Human Genetic Archive]” ran until September 7th, 2014 at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

0 Comments

|

Holly Marie Armishaw

Based in Vancouver, Canada, Holly Marie Armishaw is a contemporary artist, art writer, francophile, and world traveler. Through rigorous exploration of inspiration from international sources of art and culture, she infuses her insights with a critical eye as she discusses global trends. Both her art and writing are informed by attending a continuous array of art exhibitions, lectures, fairs and biennales, both at home and abroad. Articles

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed