|

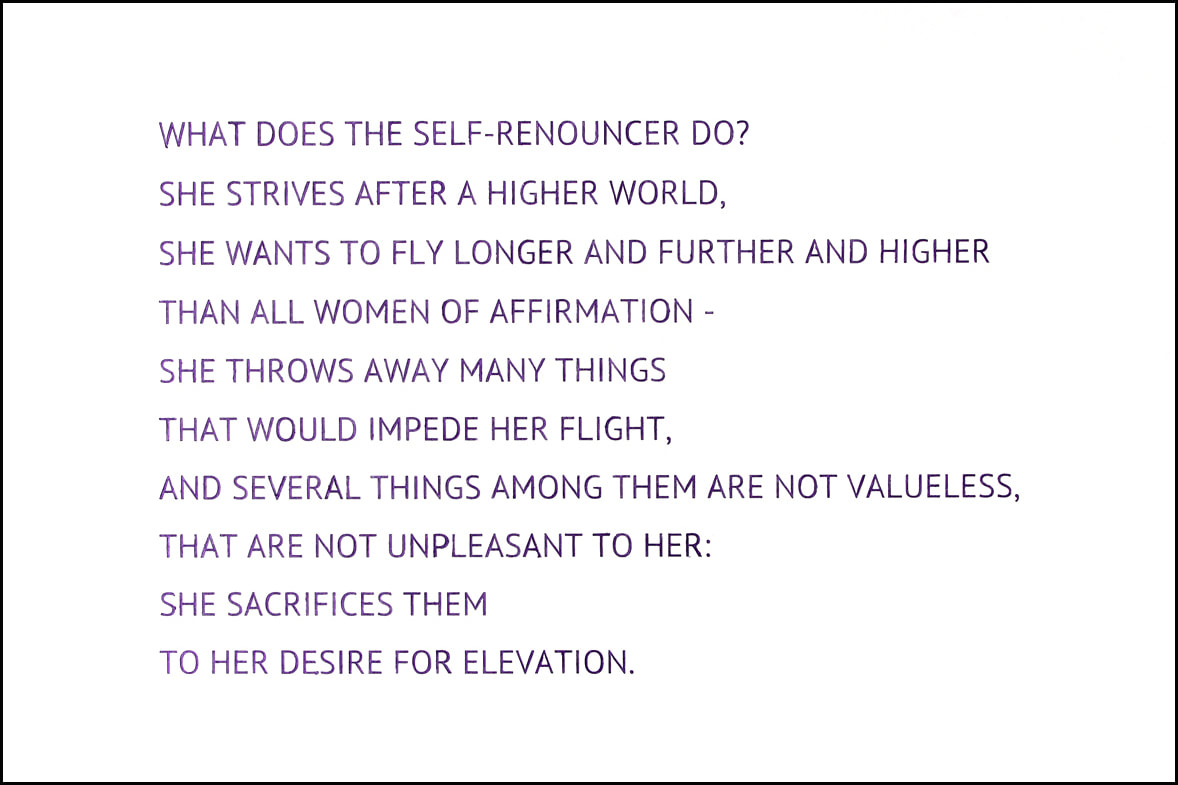

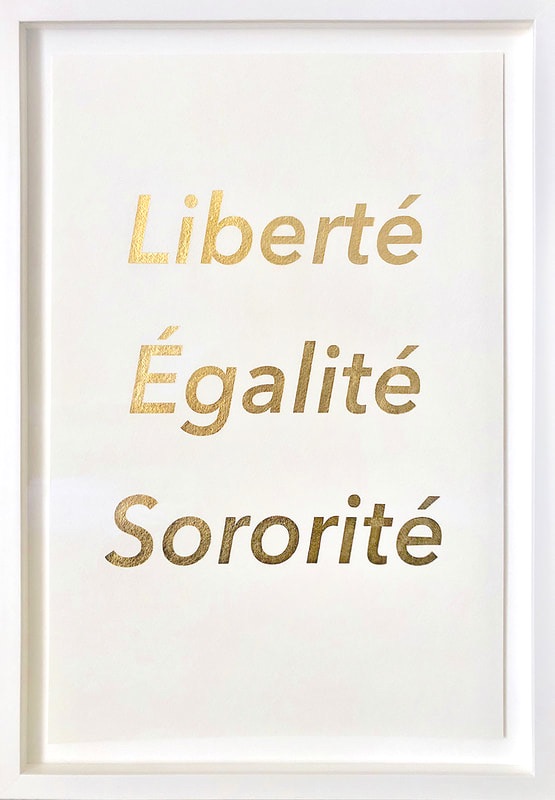

The year 2018 had been a decent one for my art career. I had rekindled my business relationship my on again-off again Vancouver-based gallery who hosted my solo show “A Feminist and a Francophile” this past November. My work had been in four contemporary art fairs in the United States throughout the year: Art on Paper - NYC, Art Market San Francisco, Seattle Art Fair, and Texas Contemporary Art Fair. I was also working with private art consultants in San Francisco and in Sacramento where my work was sold at the Crocker Museum’s art auction that summer. I had a riveting studio visit from a member of the Acquisitions Committee for the San Jose Museum of Art and the main art consultant for the offices of Google, Facebook and other noted corporations. I was shortlisted for the second year in a row for an artist’s residency in Paris. My work had finally been received into Vancouver’s prestigious Contemporary Art Gallery’s Annual Gala and Art Auction. I was invited to be in a group show in New York City at Krause Gallery early in 2019. And, my work was selling to noted collectors, including an acquisition to a prominent San Francisco based collector who had recently opened his own art foundation following on the footsteps of his maternal family, who founded the distinguished de Young Museum. All my years of hard work were finally beginning to have some momentum. On October 6 of 2018, however, it was brought to my attention via an old friend that a mutual Facebook acquaintance of ours had produced a piece of text-based art that exactly echoed the slogan of my most iconic text-based art. I have been producing several variations of my Liberté Égalité Sororité © works since early 2017, which have since become an iconic part of my practice. The artist I refer to is a popular (I am told) New York based artist. We have only met via Facebook, where we became friends in 2009 and have a fluid 60 mutual friends. Having completed thirteen different variations on my Liberté Egalité Sororité © texts over the past two years, their various renditions have made public appearances twelve times included in exhibitions, art fairs, art auctions, public installations and Women’s Marches. Two of those public appearances were in NYC. There have also been at least 35 postings of this work of mine on social media, by myself, the galleries I’ve worked with, friends, colleagues, and even Canada’s preeminent newspaper, The Globe and Mail. [Image Link 1] “It’s just three words”, you might be saying to yourself. But, when an artist’s work is truly authentic, it can never just be about three words. The previous year I had first used the phrase "Liberté Égalité Sororité" as the title of my project proposal for the Summer 2017 Georgia Fee Artist/Writer’s Paris Artist Residency. In it, I proposed the creation of a series of visual and written works on the virtually unknown women of the French Revolution. While doing research one woman in particular stood out to me; Marie Olympe de Gouges. She was an 18th century writer, activist, humanist, abolitionist and feminist. (My essay on her can be read here.) The piece of writing that she is most noted for is a feminist revision of France’s Declaration des Droits de l’Homme et le Citoyen (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the {Male} Citizen). The rights set out in the original declaration applied to only about 4.3 million French, known as “active citizens” out of a population of around 29 million. Women were deemed as “passive citizens” along with non-land-owning men, immigrants and servants. Intersectionality was not a consideration back then; those who needed equality and a voice the most, were callously swept aside. De Gouges responded with her Declaration des Droites de la Femme et la Citoyenne (Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen). To quote Olympe de Gouges “Homme, es-tu capable d’être juste?!”; translation: “Man, are you not capable of being just?!? I was absolutely thrilled when I first learned of the witty critique that de Gouges had written an astonishing two centuries before the term “feminist revisionism” had even become a part of our vernacular! I had found an ally in de Gouges nearly 250 years later. I had just completed a series of feminist revisionism text-based artworks entitled “How I Became a Feminist by Reading Nietzsche” based on my favorite quotes by Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Freud, that had made such a deep impression on me in my formative late teenage years. Like de Gouges with the Declaration of Rights, I was mostly in agreement with the content of these philosophers. Their misogynistic writings, however, had made me feel excluded as though their wisdom and inspiration were never intended to apply to me, a young woman, just as the rights of the Déclaration were intended only for men. And so, by inverting the gendered pronouns of their prose, I had made their most influential quotes my own. Using the same modus operadi that I had used in my series “How I Became a Feminist by Reading Nietzsche” I similarly executed the "Liberté Égalité Sororité" by replacing the masculine signifiers with their feminine counterparts. I also rendered them both in gold leaf and in nail polish, my signature feminine medium, painting them in various shades of mauve, eggplant and fuchsia. The work in question is a critique of France’s national motto, Liberté Égalité Fraternité, which translates into English as “Liberty Equality Fraternity/Brotherhood”. The motto is proudly displayed on French currency and every federal and municipal building across France. This protocol began in 1838, though its origins are rooted in the French Revolution of 1789. I noticed the inherent contradiction in a national motto, essentially the formula for a democratic nation, that proclaims equality yet fails to recognize over half the population. To point out this inherent hypocrisy and audacity, the idea of replacing the word “Fraternité” with its feminine counterpart “Sororité (Sisterhood)” came freely and naturally to me at this point in early 2017. It was simply a matter of combining my passions for French history and culture with feminism thus continuing the pattern of feminist revisionism in my art practice. Hence Liberté Égalité Sororité soon became a signature work and concept in my art practice - my rallying cry. The inspiration for the original choice of the word “fraternité” did not escape my notice. Having grown up in a family of Freemasons, men and women alike, on both maternal and paternal sides of the family, I understand the concept of fraternity or “brotherhood”, perhaps clearer than most. Researching and visiting important sites of Freemasons and their predecessors, the Knights Templar, has been a minor obsession of mine for over 20 years. “By the time of the French Revolution, there were some 1250 Masonic Lodges in the country (France).”[1] Freemasonry had been a prominent means by which the ideas of the Enlightenment had spread across Western Europe. The Revolution had been an effect from which the Enlightenment had been the cause. There is no wondering why the French King tried to suppress the publication and dissemination of Diderot’s Encyclopaedia, which was the equivalent of today’s Wikipedia. The Encyclopaedia empowered the middle class through the spread of knowledge acquired through the scientific revolution and the Age of Reason. If science and destroyed the authority of the church then the king could not claim to be a “divine ruler appointed by God”. The New World Order, which is demonized by conspiracy theorists, is simply the throwing off of the Ancien Régime (Ancient Regime) that was built on tyranny and autocracy. Freemasonry is often associated with a nefarious tone, which may be ill-deserved. Nefarious to whom, I ask? Secret societies were formed because of the powerful hold that the church and the monarchy held over entire nations of people. Of course people had to meet in secrecy to discuss ideals of the Enlightenment in the face of censorship and imprisonment. And, accusing them of heresy or evil was a necessary attempt to quell their power. Speaking against the church, even when using scientific logic, was speaking against the King whose position depended upon the church, which was therefore treason. Knowledge was, and still is, a dangerous threat to the balance of power. We can witness its present perceived threat in extremist communities that deny girls equal access to education even still in the 21st century. Ignorance is a weapon against the masses, which the brotherhood sought to cast off. This plight against ignorance continues today still in various forms including politics, the sciences, art and literature. [1]https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Orient_de_France Witnessing the present increasing hatred and discrimination that continues to proliferate and the depreciation for democratic ideals such as liberty and equality (through the increase in both domestic and foreign terrorism that threaten the pursuit of liberty), I turned my attention to the those who fought to develop a society built upon those core democratic principles. I began to create artwork that was not just about the roots of democracy, but about the French influence that propagated them and the women who have been largely left out of the historical picture. And so, in early 2017 I applied for the aforementioned Georgia Fee Paris Residency and was shortlisted for their international competition. Though I ended up as a runner-up, by that point I had become so passionately invested in the idea of my project that I worked out a way to make it happen nonetheless. During that summer I rented an apartment in Paris and spent June and July diligently pursuing traces of the heroines of the French Revolution who had fought so hard to support the revolutionary cause there. Not only were these women left out of the majority of history books and their artifacts lost to time, but most of them had perished in a most tragic way. While the men who supported the Revolution were honoured and glorified, the women who shared the same commitment of dedicating their lives to the revolutionary cause were restricted from public speech and office, became the source of ridicule and threats, were subjected to public beatings, rape, imprisonment, interrogation, exile, slander and worse. These women include: Olympe de Gouges, Charlotte Corday, Théroigne de Méricourt, Manon Roland, Germaine de Stæl, Clarie Lacombe and Pauline Leon, none of whose efforts to advocate for the pillars of democracy were welcomed by their “brothers”. Most of them had ended up guillotined, ironically charged as “enemies of the Revolution”. Others fled persecution to neighbouring countries or ended up in mental asylums. The majority of the men in power at the Assemblée Nationale shared something in common with the Freemasons (albeit they were 24% one and the same [2]) who both believed that women had much too delicate of a countenance to be involved in such nasty matters as politics. Their place, the Jacobins said, was to be at home caring for the raising of a young generation of Republicans. "Women were taught to be committed to their husbands and 'all his interests... [to show] attention and care... [and] sincere and discreet zeal for his salvation.' A woman's education often consisted of learning to be a good wife and mother; as a result, women were not supposed to be involved in the political sphere, as the limit of their influence was the raising of future citizens."[3] [2] https://www.kamloopsfreemasons.com/wp-content/uploads/Freemasonry-And-The-French-Revolution-1.pdf [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_the_French_Revolution During that time I put a tremendous amount of effort into searching Paris for evidence of the women who had fought so hard to support the revolutionary cause there. Not only were these women left out of the majority of history books and their artifacts lost to time, but most of them had perished in a most tragic way. While the men who supported the Revolution were honoured and glorified, the women who shared the same commitment of dedicating their lives to the cause were restricted from public speech and office, became the source of ridicule and threats, were subjected to public beatings, rape, imprisonment, interrogation, exile, slander and worse. These women include: Olympe de Gouges, Charlotte Corday, Théroigne de Méricourt, Manon Roland, Germaine de Stæl, Clarie Lacombe and Pauline Leon, none of whose efforts to advocate for the pillars of democracy were welcomed by their “brothers”. Most of these women that I tracked had ended up guillotined, ironically charged as “enemies of the Revolution”. Others fled persecution to neighbouring countries or ended up in mental asylums. Apparently the majority of the men in power at the Assemblée Nationale shared something in common with the Freemasons (albeit they were often one and the same) who both believed that women had much too delicate of a countenance to be involved in such nasty matters as politics. Their place, the Jacobins said, was to be at home caring for the raising of a young generation of Republicans. "Women were taught to be committed to their husbands and 'all his interests... [to show] attention and care... [and] sincere and discreet zeal for his salvation.' A woman's education often consisted of learning to be a good wife and mother; as a result women were not supposed to be involved in the political sphere, as the limit of their influence was the raising of future citizens." [4] [4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_the_French_Revolution My commitment to the cause of Liberté Égalité Sororité and the heroines of the French Revolution involved several photographic excursions to search for and to photograph their presence in history. My quest took me to ancient prisons, a mental asylum, the site where the guillotine was invented, the place where thousands of executions occurred, the street where an assassination by a young woman on one of the blood-thirsty radical revolutionaries happened, the former site of the Templar fortress, a national Masonic lodge, clandestine rooms atop restaurants where covert operations were discussed, museums, official historic institutions, and even to a cobweb infested staircase beneath my apartment that led to the underground tunnels/catacombs. These and other journeys, alongside research through countless documentaries, books and articles, all carried out en Français, reveal the legwork, passion and dedication behind my creation of the Liberté Egalité Sororité artworks. As the Women's Movement sweeps across the globe I regard it as unfinished business not just for ourselves, but for the rights of those whose lives were swept under the carpet in the past, and as a battleground for the women of generations to come. The past, present and future are inextricably linked, hence, my interest and practicing feminist revisionism in my art since 2011. A friend and colleague of mine declared "He’s capitalized on the #MeToo movement by stealing from someone whom the movement is meant to protect!", upon hearing about the appropriation of my "Liberté Égalité Sororité" work regarding the aforementioned NYC artist. Maynard Monroe has appropriated my artwork, a rallying cry for female equality, for his own personal gain and twisted the context to cover his tracks. This artist’s portfolio suggests that this isn't the first time he's "borrowed" phrases from other artists for his text-based work. That, and his social media also suggests that he doesn't have any interest in France or French culture, nor speaks French. But the most telling fact is that what an artist’s work will always betray - patterns. Feminist revisionism and the inverting of gendered pronouns are devices that this artist has never used in his work before this piece; it simply doesn't fit his pattern. Despite the hypocrisy of claiming to be a feminist, please, tell me again how this is "an original M.M. work" and not simply a nonchalant appropriation of a Facebook friends’ work because she has less visibility and is therefore fodder for someone of higher repute and lesser integrity. The art world asks why there aren’t more successful women artists. Perhaps more women, of the past, present and future, would achieve their lofty ambitions if men weren't perpetually taking from us and thwarting our career attempts. Whether it be stealing our sense of autonomy, crippling us with trauma, or appropriation of intellectual property, enough is enough! Perhaps my sentiment is best expressed by the Notorious RGB (Ruth Bader Ginsberg): “All we ask of our breathren is that they take their feet off our necks.” - Holly Marie Armishaw (2019) Timeline of Liberté Égalité Sororité public appearances. Suggested Readings: Moore, Lucy. Liberty – The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France. Harper Collins Publishers, 2006. Birch, Una. Secret Societies - Illuminati, Freemasons and the French Revolution. Ibis Press, 2007. Poirson, Martial. Amazones de la Revolution (Des Femmes dans la tourmente de 1789). Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2016. Blanc, Olivier. Olympe de Gouges – Des Droits de la Femme à la Guillotine. Éditions Tallandier, 2014. https://www.kamloopsfreemasons.com/wp-content/uploads/Freemasonry-And-The-French-Revolution-1.pdf

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Holly Marie Armishaw

Based in Vancouver, Canada, Holly Marie Armishaw is a contemporary artist, art writer, francophile, and world traveler. Through rigorous exploration of inspiration from international sources of art and culture, she infuses her insights with a critical eye as she discusses global trends. Both her art and writing are informed by attending a continuous array of art exhibitions, lectures, fairs and biennales, both at home and abroad. Articles

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed