|

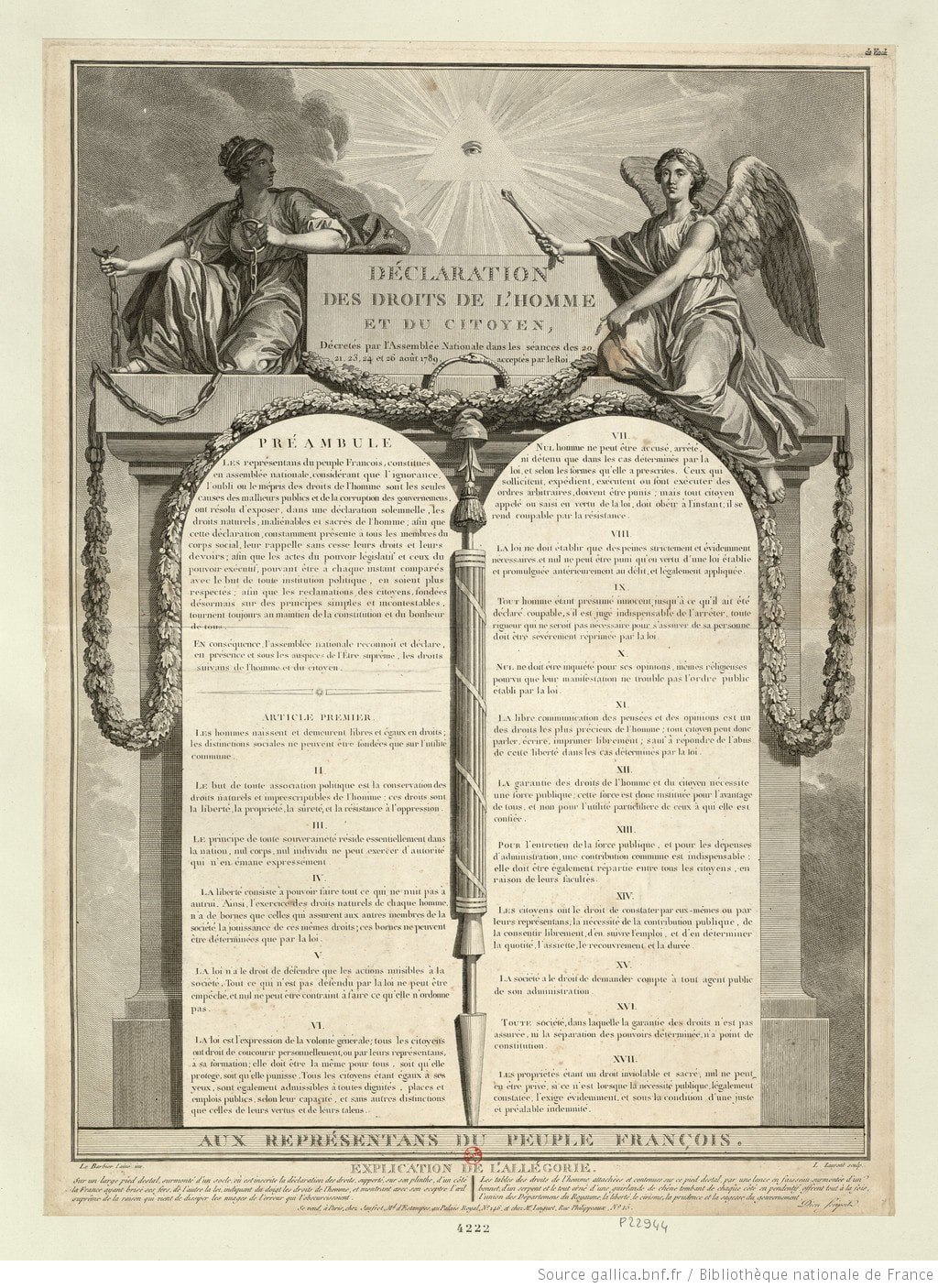

Olympe de Gouges was arguably the most important woman of the French Revolution. Although not as well known as others, particularly in English speaking circles, de Gouges produced a body of written work that expressed important ideals on human rights that were quite radical during that time, but are taken for granted in most democratic countries today. Her clarity of recognizing injustice was unparalleled in late 18th century France. She acted with a fearless moral compass on behalf of oppressed persons without distinction of class, race or gender, whether they were colonized slaves or the king of France. Armed with a quill pen as her only weapon, de Gouges headed into the bloody Reign of Terror and nothing short of the guillotine would deter her bravery in fighting for human rights. The outbreak of Revolution was a source of great optimism for the women of Paris in hopes that the changes to be gained would be to the benefit of all persons, including themselves. Olympe De Gouges hopes for the Revolution differed from those of the women who marched on Versailles in that their demands were aimed at immediate needs like the securing of bread and wheat, while de Gouges had loftier sights such as gaining long-term political equality for women. This gained her a reputation as one of the most notable and earliest feminists of France. One of the most pivotal events in the French Revolution was indeed the Women’s March on Versailles on October 5th and 6th of 1789, which pressured King Louis XVI into finally signing the Declaration of Rights and in bringing him and the royal family to the Tuileries Palace in Paris where they would be at the mercy of the Revolutionaries. However, the rights that those women had marched and fought for would not be their own. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) did not include women, nor even consider their needs. Women were categorized as passive citizens, meaning that they were unable to vote and excluded from the rights laid out in the Declaration. Likewise, men who were servants also considered passive citizens. Only land-owning men were afforded the rights of “universal” suffrage. Ironically, this monumental document was inspired by and Jean Jacques Rousseau and cited his Enlightenment principle that “all men are born and remain free and equal in rights”. Article VI of the Declaration states that “The law is the expression of the general will” and yet excludes over half of the general population. In fact, the estimated population of France at that time was approximately 29 million people, but only 4.3 million Frenchmen were extended the rights of active citizens. This document, rife with contradictions, was written by bourgeoisie men for bourgeoisie men. Laughably, Article XII states “The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.” And so, with her sharp intellect, Olympe de Gouges attacked the Declaration using the wit and language of an Enlightenment philosopher, releasing it’s antithesis in 1791, the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne). As the National Assembly worked to establish new laws to replace those of the old regime (l’Ancien Regime), Olympe de Gouges fought to address them with demands, which might extend natural law to all French people, including women. In the name of liberty and equality she wrote 40 plays, two novels and over 90 political pamphlets. Her recommendations, contained within these writings, included:

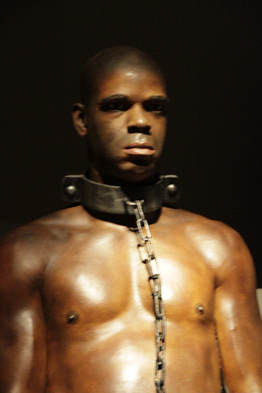

From her biography it can be deduced that Olympe de Gouges unwavering commitment to combat for those who were oppressed was influenced by her own life as a marginalized individual. Born in 1748 as Marie Gouze to a petite bourgeoisie family in Montauban of South Western France, she was the illegitimate child of a man of power and wealth, Jean-Jacques Lefranc, Marquis de Pompignan. Her biological father, however, refused to publically acknowledge her as his daughter. The ill treatment of both herself and her mother compelled Marie to later plead for rights such as child-support on behalf of illegitimate children and their widowed mothers. Married off at the age of 16 to a local innkeeper of Montauban, it was a most unhappy marriage for Marie, no doubt, inspiring her to later fight for women’s right to divorce. The parallels are endless. Olympe de Gouges relentless pursuit of equality being significantly based on personal experience foretells the second wave feminism of the 1970’s whose rallying cry was “The personal is political”. “The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized and reflective of a sexist power structure.”[1] Widowed by age 18, in 1770, she and her son Pierre moved to Paris where she reinvented herself as Olympe de Gouges, an amalgamation of her mother’s and father’s names. Although she had long-term partners in Paris, de Gouges refused to re-marry as doing so would limit her political freedom and allow a husband ownership over her intellectual property. Inspired by her biological father who was regarded also as a man of letters, de Gouges followed in his footsteps, leading her to the salons of Paris and literary circles. As a young women of the French provinces, de Gouges had received only a nominal education by local nuns. The French dialect of Montauban was also very different from that of Parisians, and so her grasp of the language, both spoken and written, was indeed a challenge. Likely it was this challenge that inspired de Gouges to fight for the equal education of girls. Furthermore, it was argued that women could not be allowed to vote because they weren’t educated and therefore could not make educated decisions. So by keeping girls from being educated, they were also thereby kept from voting, a practice that is still prolific in some parts of the world today. De Gouges fight for women to hold political equality foretold the fight for suffrage in the 19th century, which heralded the first wave of feminism. However, it would not be until 1944 that women in France gained the right to vote. "Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum." Olympe de Gouges Acknowledged mostly as a feminist, Olympe de Gouges was, above all, a humanist. In 1784 she wrote the play Zamore and Mirza or The Enslavement of the Blacks (Zamore et Mirza ou l’Eclavage des Noirs). Sadly, the play was shut down after only three performances due to the brawls that ensued between abolitionists and businessmen who had an interest in the slave trade. Ten years later, de Gouges fight was reconciled when slavery in the French colonies was abolished in 1794. Unfortunately though, in 1804 Napoleon reinstated slavery in the sugarcane growing colonies under regulation of the Napoleonic Code. But by the 1850’s France, Britain the United States had abolished and criminalized slavery. However, the slave trade is still alive today as seen in CNN’s 2017 exposé of Libya, proving that this dark stain on humanity is one not easily eliminated. Extending her ideology of the right to a fair trial to be extended to all persons, was to be her downfall. Stripped of his title as king, Louis XVI had become simply Louis Capet, and was facing trial for treason against France. De Gouges, who was also against capital punishment, offered to act as his legal counsel. She stated that “As king, I believe Louis to be in the wrong, but take away this proscribed title and he ceases to be guilty, in the eyes of the republic”.[2] Her alignment with the moderate Girondins was barely tolerable, but what was perceived as her support for the monarchists, had crossed the line tantamount to being an “enemy of the Revolution”. In one of her most memorable statements, Olympe de Gouges declared “women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum". Sadly, while she would never be permitted to enjoy the latter, her prolific career as a playwright and human rights activist would come to an end at the drop of the blade on November 3, 1793. - Holly Marie Armishaw (2017) [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_feminism [2] http://www.olympedegouges.eu/defenseur_officieux.php Bibliography:

Blanc, Olivier. Olympe de Gouges – Des Droits de la Femme à la Guillotine. Éditions Tallandier, 2014. Poirson, Martial. Amazones de la Revolution (Des Femmes dans la tourmente de 1789). Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2016. Moore, Lucy. Liberty – The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France. Harper Collins Publishers, 2006. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_the_Rights_of_Man_and_of_the_Citizen https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympe_de_Gouges https://www.loc.gov/law/help/inheritance-laws/france.php https://bonjourparis.com/history/olympe-de-gouges/ http://olympedegougesinfo.weebly.com/background.html http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/293/ http://www.iep.utm.edu/gouges/

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHolly Marie Armishaw ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed