The Philosophy of Self-Portraiture in Contemporary Art

Introduction

Philosophy addresses the non-essential, but intriguing question of – “why?”

This essay addresses various reasons why artists may choose to use self-portraiture in their art, particularly in the art of contemporary photography.

Necessity and Control – The Practical Aspects

Often we as emerging artists begin our practice with minimal resources at our disposal. We resort to using whatever materials available, through whatever means possible. Without the financial resources to hire professional actors or models to pose as subjects for our works, artists often rely on themselves or on the assistance of friends to avoid complications with model release forms and financial compensation. If the work that we want to create requires the human figure or face, nothing could be more accessible than our own bodies. Artists will quickly find that the model who is most reliable, committed, willing to push themselves to great lengths, anxious to experiment, and to most easily grasp the concept of the artist’s direction and express their personal aesthetic, is themselves. After all, no one can articulate your thoughts better than you can. The primacy of thought leaves no chance of misinterpretation.

There is an essential element of “control” in the art of self-portraiture. We control what details are included in the final works and what details are excluded. For a moment, we seize control of time and space. We control the decisive moment that is captured and the setting in which we are contained. The artist becomes director in the clip in which they are the lead actor. The self-portrait can become a major exercise in independent production. Particularly in the case of photography, the artist’s roles may include that of location scout, researcher, set designer, props manager, lighting designer, director of photography, special effects artist, aesthetician, wardrobe manager, hairstylist, makeup artist, actor, director, camera operator, digital editor, and Photoshop expert. As the artist advances in the stages of their career, some of these roles may be delegated to assistants, but the original modous operandi generally remains the same. The resulting work is a pure, independent expression of the artist’s vision.

Consider the elaborate works by Cindy Sherman or Rodney Graham, or even my own similarly independent productions. However, even in the opposite style of self-portraiture, within the most candid and spontaneous works, there is also a conscious element of control.

Philosophy addresses the non-essential, but intriguing question of – “why?”

This essay addresses various reasons why artists may choose to use self-portraiture in their art, particularly in the art of contemporary photography.

Necessity and Control – The Practical Aspects

Often we as emerging artists begin our practice with minimal resources at our disposal. We resort to using whatever materials available, through whatever means possible. Without the financial resources to hire professional actors or models to pose as subjects for our works, artists often rely on themselves or on the assistance of friends to avoid complications with model release forms and financial compensation. If the work that we want to create requires the human figure or face, nothing could be more accessible than our own bodies. Artists will quickly find that the model who is most reliable, committed, willing to push themselves to great lengths, anxious to experiment, and to most easily grasp the concept of the artist’s direction and express their personal aesthetic, is themselves. After all, no one can articulate your thoughts better than you can. The primacy of thought leaves no chance of misinterpretation.

There is an essential element of “control” in the art of self-portraiture. We control what details are included in the final works and what details are excluded. For a moment, we seize control of time and space. We control the decisive moment that is captured and the setting in which we are contained. The artist becomes director in the clip in which they are the lead actor. The self-portrait can become a major exercise in independent production. Particularly in the case of photography, the artist’s roles may include that of location scout, researcher, set designer, props manager, lighting designer, director of photography, special effects artist, aesthetician, wardrobe manager, hairstylist, makeup artist, actor, director, camera operator, digital editor, and Photoshop expert. As the artist advances in the stages of their career, some of these roles may be delegated to assistants, but the original modous operandi generally remains the same. The resulting work is a pure, independent expression of the artist’s vision.

Consider the elaborate works by Cindy Sherman or Rodney Graham, or even my own similarly independent productions. However, even in the opposite style of self-portraiture, within the most candid and spontaneous works, there is also a conscious element of control.

Consciousness vs. Self-Consciousness

The concept of self-portraiture is inherently linked to the concept of self-consciousness. And, the concept of portraiture, if not even art itself, is linked to consciousness. Art making can never truly be an “automatiste” process. There is always a conscious element of involvement. Lets suppose we were to consider robots that can paint. Alexander McQueen in his spring/summer 1999 runway show used just such robots. Can an unconscious entity create art? Though the robots themselves may not be conscious of painting, the sheer observation of painting (by others) and defining it as such, makes it so. But, in order to perform the act of painting, the robots have to be programmed to perform the actions required of painting. The consciousness therefore lies in the programmer rendering the robots seemingly automatic actions possible.

Even the use of randomness in the creative process reflects a conscious decision to use randomness as criteria for the work. Every stroke of a paintbrush, or click of the shutter at any particular time and place reflects a conscious decision. Art is the reflective result of consciousness. The fact that humans make art is one of the few traits that set us apart from most other species.

The concept of self-portraiture is inherently linked to the concept of self-consciousness. And, the concept of portraiture, if not even art itself, is linked to consciousness. Art making can never truly be an “automatiste” process. There is always a conscious element of involvement. Lets suppose we were to consider robots that can paint. Alexander McQueen in his spring/summer 1999 runway show used just such robots. Can an unconscious entity create art? Though the robots themselves may not be conscious of painting, the sheer observation of painting (by others) and defining it as such, makes it so. But, in order to perform the act of painting, the robots have to be programmed to perform the actions required of painting. The consciousness therefore lies in the programmer rendering the robots seemingly automatic actions possible.

Even the use of randomness in the creative process reflects a conscious decision to use randomness as criteria for the work. Every stroke of a paintbrush, or click of the shutter at any particular time and place reflects a conscious decision. Art is the reflective result of consciousness. The fact that humans make art is one of the few traits that set us apart from most other species.

Art making has become one of the standards for which we test for consciousness. While scientists have worked with primates testing for the ability to create art, they have found that what they produce are mere pictorial representations at best. So how are we any different? While most of us have seen videos of cats or chimps that paint, it is rare that they will ever produce a self-portrait. However, at an elephant park in Thailand elephants have been seen by many and recorded painting portraits of elephants. Though we cannot be sure if their intent is to paint a portrait of themselves or of some other elephant, the question of the existence of self-awareness among other species has been raised through this portrait vs. self-portrait debate. All sentient beings are conscious, but not all sentient beings are self-conscious, a standard measure of advanced intelligence.

Identity Issues and Autobiography

If art making always involves conscious decision-making and self-portraiture reflects self-consciousness, then what is the message or meaning of self-portraiture? Why do certain artists decide to create self-interpretations or visual archives of their presence and decidedly so in a particular time and space? The question answers itself. The self-portrait declares “I exist”.

The notion of a portrait is intrinsically linked to that of identity. Through self-portraiture, we become representational figures in our works, a first-person “poster child” for whatever identities our image carries with it. Contemporary art draws largely on the signifiers of identity as subject for discussion. Artists, in their self-awareness utilize their signifiers, whether intimate and personal, specific to gender, race, class, culture, sexual orientation or transfiguration, for intellectual discourse. The complexities of the definition of self are played out on the metaphorical and literal canvas.

Whether abstract, subtle, or intimately detailed, the self-portrait is inherently autobiographical. Many artists experiment with negating the self through hiding or masquerading within their works. In light of this practice, I am reminded of the philosophical thought experiments where one considers whether s/he would still be herself if s/he received a heart transplant. While most of us would still think that we are ourselves after a heart transplant, the same cannot be said if we were to consider a similar question, but with a brain transplant. Furthermore, the performance works of French artist ORLAN, in which she undergoes cosmetic surgeries, repeatedly altering her facial construction, also questions the locus on which we place self-identity. No matter how much we attempt to distort or abstract our appearance, we are trapped within our selves as our identity lies not in any one physical feature or set of characteristics, but in the conscious entity behind these. Ultimately, any conscious representation of the self, disguised or not, can be classified as a self-portrait.

If art making always involves conscious decision-making and self-portraiture reflects self-consciousness, then what is the message or meaning of self-portraiture? Why do certain artists decide to create self-interpretations or visual archives of their presence and decidedly so in a particular time and space? The question answers itself. The self-portrait declares “I exist”.

The notion of a portrait is intrinsically linked to that of identity. Through self-portraiture, we become representational figures in our works, a first-person “poster child” for whatever identities our image carries with it. Contemporary art draws largely on the signifiers of identity as subject for discussion. Artists, in their self-awareness utilize their signifiers, whether intimate and personal, specific to gender, race, class, culture, sexual orientation or transfiguration, for intellectual discourse. The complexities of the definition of self are played out on the metaphorical and literal canvas.

Whether abstract, subtle, or intimately detailed, the self-portrait is inherently autobiographical. Many artists experiment with negating the self through hiding or masquerading within their works. In light of this practice, I am reminded of the philosophical thought experiments where one considers whether s/he would still be herself if s/he received a heart transplant. While most of us would still think that we are ourselves after a heart transplant, the same cannot be said if we were to consider a similar question, but with a brain transplant. Furthermore, the performance works of French artist ORLAN, in which she undergoes cosmetic surgeries, repeatedly altering her facial construction, also questions the locus on which we place self-identity. No matter how much we attempt to distort or abstract our appearance, we are trapped within our selves as our identity lies not in any one physical feature or set of characteristics, but in the conscious entity behind these. Ultimately, any conscious representation of the self, disguised or not, can be classified as a self-portrait.

Performance and Documentation

Although the use of oneself in contemporary visual art is not that common of a practice, in other arts forms it is so commonplace that we have failed to perceive it as such. It has become an example in which self-portraiture hides in plain sight. I am referring to the performing arts. Think of your favourite musician, whether a pop-singer, guitar player, or operatic soprano. Consider a dancer, dance troupe or your favourite film actors. Each of these artists appear in their own art. They tell stories with their bodies and voices through the art of performance.

Often self-portraits in contemporary photography are a documentation of a performance whose sole audience is the camera. Drawing upon the aforementioned “production-like” quality of self-portraiture, specifically photographic, these images take the form of “film stills”. Unlike a true still from a feature-like film however, the performance and documentation’s sole purpose is the creation of the still image as a final work. Any narrative that surrounds the image is left to the realm of the imagination, evoked by a myriad of visual signifiers chosen by the self-portrait artist. This genre of self-portraiture was popularized by the series of the same name “Film Stills” by Cindy Sherman in the late 70’s. The function of the staged photographic film still may be traced back as early as Henry Peach Robinson’s “Fading Away” from 1858. Photographic self-portraits can be traced back even earlier than that (circa 1839 by Robert Cornelius) but no wonder with the influence that painting has had on the art of photography. Pictorialism is of course the art of creating an image, rather than recording it and has re-gained popularity in photography since Sherman’s “Film Stills”.

Although the use of oneself in contemporary visual art is not that common of a practice, in other arts forms it is so commonplace that we have failed to perceive it as such. It has become an example in which self-portraiture hides in plain sight. I am referring to the performing arts. Think of your favourite musician, whether a pop-singer, guitar player, or operatic soprano. Consider a dancer, dance troupe or your favourite film actors. Each of these artists appear in their own art. They tell stories with their bodies and voices through the art of performance.

Often self-portraits in contemporary photography are a documentation of a performance whose sole audience is the camera. Drawing upon the aforementioned “production-like” quality of self-portraiture, specifically photographic, these images take the form of “film stills”. Unlike a true still from a feature-like film however, the performance and documentation’s sole purpose is the creation of the still image as a final work. Any narrative that surrounds the image is left to the realm of the imagination, evoked by a myriad of visual signifiers chosen by the self-portrait artist. This genre of self-portraiture was popularized by the series of the same name “Film Stills” by Cindy Sherman in the late 70’s. The function of the staged photographic film still may be traced back as early as Henry Peach Robinson’s “Fading Away” from 1858. Photographic self-portraits can be traced back even earlier than that (circa 1839 by Robert Cornelius) but no wonder with the influence that painting has had on the art of photography. Pictorialism is of course the art of creating an image, rather than recording it and has re-gained popularity in photography since Sherman’s “Film Stills”.

Truth or Fantasy?

Documentation has become an essential element in almost any art form. In a photographic self-portrait, documentation becomes an art unto itself. Photography holds a privileged position in art with its unique ability to mirror reality with such accurate and detailed precision. However, artists who are critical of photography’s inherently documentary like capabilities use the medium to question our perceptions of reality. Its realistic nature is often exploited by elaborate fictions that are created within the photograph, thereby critiquing it’s shallow stigma of photography being a mere recording device.

But are these ruses simply critiquing the medium and challenging our perceptions of reality? How does this relate when combined with self-portraiture? The photograph then becomes a stage on which to enact our stories. Often like reality, there is no singular truth, and what one perceives as fiction may also contain certain elements of truth, albeit often hidden. Renowned actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski noted, “Characterization is the mask that hides the actor-individual. Protected by it he can lay bare his soul down to the last intimate detail.”

Documentation has become an essential element in almost any art form. In a photographic self-portrait, documentation becomes an art unto itself. Photography holds a privileged position in art with its unique ability to mirror reality with such accurate and detailed precision. However, artists who are critical of photography’s inherently documentary like capabilities use the medium to question our perceptions of reality. Its realistic nature is often exploited by elaborate fictions that are created within the photograph, thereby critiquing it’s shallow stigma of photography being a mere recording device.

But are these ruses simply critiquing the medium and challenging our perceptions of reality? How does this relate when combined with self-portraiture? The photograph then becomes a stage on which to enact our stories. Often like reality, there is no singular truth, and what one perceives as fiction may also contain certain elements of truth, albeit often hidden. Renowned actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski noted, “Characterization is the mask that hides the actor-individual. Protected by it he can lay bare his soul down to the last intimate detail.”

The popularity with artists masquerading in self-portraiture may be attributed to our inability to be content playing only one role in art, and in life. As complex being with rich, inner lives, one role is hardly satisfying. We are not easily defined by a single identity. The self-portrait enables us to create a realm where we can express our past-selves, repressed selves, desires, maladies of the mind, intellectual interests or to fantasize about being someone altogether different than ourselves. The masqueraded self-portrait can be an escape into a world where we have full creative control – not surprising in a reality where we can often feel that we have little control over. We crave the world where we are free to be anyone that we chose to be.

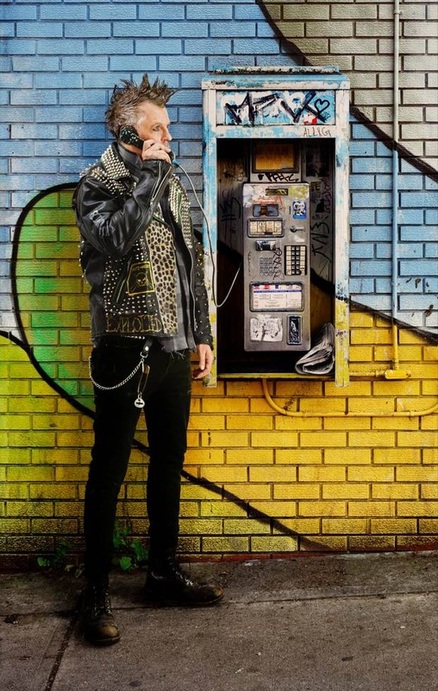

Let’s consider the self-portraiture of Vancouver artist Rodney Graham. He has appeared in his own works as a myriad of characters, from Marlboro Man, bohemian, aging punk rocker, painter, urban dandy, anti-hero, convict/law-breaker, poet, chef, lighthouse keeper, Hitchcock antagonist, deserted islander, drug user, painter and more. Though these self-portraits may be disguised as masquerading, any one that knows even a bit about the real Rodney Graham, can see elements of truth in these representations. These self-portraits contain a fascinating irony with their self-deprecating humour as Graham reveals many of his semi-incomplete dreams to his viewers through his art.

Let’s consider the self-portraiture of Vancouver artist Rodney Graham. He has appeared in his own works as a myriad of characters, from Marlboro Man, bohemian, aging punk rocker, painter, urban dandy, anti-hero, convict/law-breaker, poet, chef, lighthouse keeper, Hitchcock antagonist, deserted islander, drug user, painter and more. Though these self-portraits may be disguised as masquerading, any one that knows even a bit about the real Rodney Graham, can see elements of truth in these representations. These self-portraits contain a fascinating irony with their self-deprecating humour as Graham reveals many of his semi-incomplete dreams to his viewers through his art.

The self-portrait could be likened to a literary work written in the first-person. It is only natural to tell our experiences in the first-person, as observed in our typical speech pattern. The self-portrait artist goes beyond this, creating a visual literary work where he or she is the protagonist or antagonist. And just as one cannot write the great American novel without first living it, it follows that one cannot produce a great work of art without first experiencing the life to reflect it.

Using their personal lives as subject matter for their art, some artists prefer to work with straight photography, from a very direct first-person experience. Their blatantly honest images simultaneously demand and defy us to look at them. The capacity of photography to tell the truth is used as a diary, archiving particular moments in time for means of reflection. Another threshold is crossed through this photographic method – the threshold between private and public. The very specificity of diaristic self-portraits paints a vivid picture, casting light on issues that are often kept in the dark. The self-portraits of Nan Goldin come to mind, illuminating the life of her and her friends, where drug use, AIDs and domestic abuse and violence were typical. This genre of self-portraiture can be both an enlightening and a cathartic experience. The veil of denial is lifted concurrently with the opening of the shutter.

Extension of Self and Immortality

Photography has an ability like no other, to capture a realistic rendering of an individual. So much so, that when we share a photograph, we often say, “This is (insert name here)”. The photograph is a 2D clone of that individual. When taken to the level of contemporary art, we might say “Marina Abramovic is in the MoMA” which could mean either she, the living, breathing artist is in the gallery, or we could mean her work. Further yet, we could mean a portrait or self-portrait of her. Our art, whether our likeness is presented within it or not, is an extension of ourselves. If successfully planted into the fabric of history, this extension of self will surpass our physical existence. Just as many attempt to extend their existence into the future through having a family of future generations that carry on both their DNA along with values and traditions, we as artists aim to extend our mental selves into the future, injecting our art works with our own ideologies and mental selves. This theory could be ascribed to any role of creative producer – architect, philosopher, composer, painter, etc.

The previously mentioned Marina Abramovic, known mostly as a performance artist, was chosen for mention because of the proximity of performance art to self-portraiture. Logically, self-portraiture is therefore closely linked to performance, and therefore to the body. And what is the body if not a living organism prone to birth, growth, entropy and eventually – death? The self-portrait acts simultaneously as a memento mori, and as a vehicle for immortality. Most of us expect to live no longer than 100 years of age. Given that even the earliest photographs are still in existence, albeit in a fragile state, and given the advances and assurance of photographic technologies archival standards today, we can safely assume that a photograph will exist far beyond our own lifespan. For the artist who is both knowledgeable in the medium of photography and is self-aware, self-portraiture is a conscious exercise in existentialism.

As a conscious act, we document our inner and outer selves, meticulously curating the facets of our existence, both the painful and the triumphant, that we wish to leave behind in the world. And from these archives we hope that others can learn – to look inside themselves, to reconsider their stereotypes of those around them, to remind ourselves of the brevity of youth, beauty and life itself, to challenge previous modes of perceptions of reality, and to question where in fact our very identity lies and how it is constructed. And, like reality, there is no sole explanation for why artists create self-portraiture; there are many truths. With the camera we hold a mirror up to the world in the hopes that each viewer will, as Aristotle says “Know Thyself”.

Not only is the empress wearing clothes, but she is wearing many layers of them. (Holly Marie Armishaw)