Perception Studies Through the Development of Photography

With an air of dissatisfaction regarding the over-saturated mass-proliferation of instant digital images, I find myself, as a photographer, turning elsewhere. Meticulously cutting and pasting to create works that challenge our perceptions of reality and illusion, I continue to use a similar modus operandi as I have in Photoshop for so many years. However, I am now producing work mostly through analog forms using simple materials like photographs, mirrors and (unseen) balsa wood. A hybrid form of illusion, combining both tactile illusory objects such as mirrors, combined with the secondary illusion of the photograph, one’s perception and previous notions of what constitutes a photographic work are challenged. Mimicking the digital composite layer of my past work, print layers are spaced apart, creating a further play on the photographic 2D illusion of a 3D world.

Let us remember that the camera as we know it today, would not be possible without the invention of the plate-glass mirror. In my last series I focused on the French Revolution and began using mirrors in my work. The French Revolution fell upon the footsteps of the Age of Enlightenment – an age where great strides were made in the sciences as plate glass allowed humankind to create lenses that enabled them to see the most minute structure of life-forms through the invention of the microscope and conversely, to perceive a vast cosmos far beyond our greatest expectations through the invention of the telescope. Our perception of ourselves in the larger scale of the universe was forever altered with the advent and explorations of plate glass. This perception was furthered still when silver was added to one side of the glass, enabling the first plate-glass mirrors to usher in a new sense of self-awareness and a perception that was rarely before known.

The French competed fiercely against the Venetians to conquer the market on this great new invention. The famous Hall of Mirrors of Versailles, commissioned in 1678 during the reign of Louis the XIV, was a testament to the wealth and power of the French court. The hall boasted 17 arcaded windows, each containing 21 plate-glass panels. Production of glass was difficult, and still limited in the scale of each panel. Mullions were built between multiple small panels to enable them to be joined together into a lager whole. This is the origin of what we know today as French Doors. Opposite the 17 arcaded windows in the Hall of Mirrors were an equal number of awe-inspiring, paneled plate glass mirrors. Mirrors were one of the most expensive architectural and decorative elements of the time, and yet graced nearly ever room in of the Palace of Versailles. When Marie Antoinette came to Versailles to be married at the age of 14, she would have been constantly subjected to the scrutiny of the mirrors, which offered her and others a unique perspective – they had the unique experience of seeing themselves as others saw them.

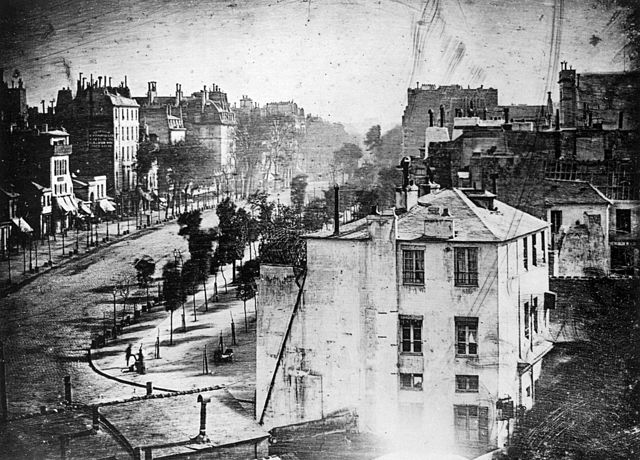

Some 50 years after the French monarchs were killed scientists were working to apply plate-glass to a new invention that would change their lives forever. Louis Daguerre and others worked feverishly to freeze or fix the image that they saw in the mirror and through the camera lucida. Daguerre had already become known for his “Daguerre Dioramas” which use multiple layers of painted fabric and differentiated lighting to depict theatrical-type scenes for entertainment value. By 1838, continuing to work with light and illusion, he had realized his goal of “fixing“ the photographic (light-writing) image and sold the patent to his “Daguerreotype” process to the French government to make available to it's people. The Daguerreotype process created a photographic image fixed onto a mirror-like surface. When the process was released to the public in the early 1940’s they found that the chemistry was not yet light-sensitive enough to provide a reasonably short enough exposure to be conducive to portraiture. And so, the earliest Daguerreotypes were typically views of Parisian streets or rooftops, as shot from the photographers apartments: “..Everywhere cameras were trained on buildings. Everyone wanted to record the view from his window, and he was lucky who at first trial got a silhouette of rooftops against the sky. He went into ecstasies over chimneys, counted over and over roof tiles and chimney bricks, was astonished to see the very () mortar between the bricks…”[1]

Often these rooftop views contained partial views of the photographer’s interior as well. Over time, plate-glass had decreased in cost and French windows were more accessible to the people of Paris. These mullioned plate-glass windows became so widely used in French architecture that they have become iconic and are still popular today. Aside from their aesthetic charm, they provide shelter from the exterior elements, while simultaneously letting light inside and allowing the inhabitant to enjoy the constantly changing theatrical-like scene, not unlike the Daguerre Diorama, which plays out in front of them. As day turns to night, summer turns to winter, and era turns to era, the formal elements of the setting remain relatively constant.

Although mostly leaving behind self-portraiture, which has been a key theme in my past work, one direction this new series still explores are adaptations of other forms of self-awareness, their history, and their relationship to photography; therefore the mirror is particularly vital in this aspect.

All of the photographs used in these works are my own and were shot during my many stays in France. The rooftop views were taken during various periods when I stayed in rental apartment in Paris. This installation is in essence a reproduction of my own space, or combination of spaces, that I use for contemplation and creative processes. The viewer is invited to enter my pied-à-terre and to view the work in a reproduction of its original context, through the lenses of its origins.

- Holly Marie Armishaw (January 3rd, 2015)

[1] Marc Antoine Gaudin, Taite practique de la photographie, no. 40 (Paris: JJ Dubochet et Cie., 1844), pp. 6-7. From The History of Photography, Beaumont Newhall, page 23.